|

|

How to Save Your Own Life

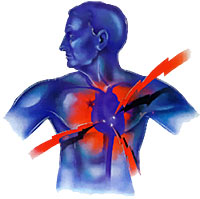

How to Save Your Own LifeI was once an Advanced Emergency Medical Technician (A-EMT). Over a period of six years and thousands of ambulance runs, I handled several hundred cardiac emergencies, many of them cardiac arrests. Unfortunately, very few of these people survived. Even though I was able to administer drugs and defibrillate once we arrived, too much damage had already occurred because (1) nobody on the scene knew how to perform CPR, and (2) the victim often waited too long to call for help, then lapsed into full cardiac arrest. If you don't know how to perform CPR, take a course and learn. It's not a big deal. If you need motivation, please know that the most likely person you'll ever perform CPR on will be someone close to you: a spouse, parent, child, or friend. If they NEED cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and you don't know how to give it, they are probably going to die. The Red Cross and many local agencies provide free CPR training courses. Now I'll tell you how to save your own life: know the symptoms of a heart attack and don't be afraid to call for help even if you're uncertain. Denial is a huge killer. What you do in the first hour is crucial. Here's why (the simplified version): The heart is a muscle. It needs a continuous flow of blood or the muscle itself will die. Once that happens, the heart stops pumping and the rest of you dies, starting with your brain (only four minutes without a supply of oxygenated blood and brain damage begins). Fortunately, there are great new clot-busting drugs and procedures like balloon angioplasties that when administered within the first hour of a heart attack, prevent damage to the heart muscle. Over a million Americans suffer a heart attack each year. About 460,000 of those heart attacks are fatal. About half of those deaths occur within one hour of the start of symptoms and before the person reaches the hospital. Many people think a heart attack always comes on suddenly and dramatically the "movie heart attack" where a victim clutches his chest and falls to the floor. While some heart attacks are sudden and intense like this, the majority start slowly and less spectacularly. It's easy to mistake these initial signs for something else, so it's extremely important to know the possible symptoms of a heart attack. Warning Signs of a Heart Attack

Bottom line: even if you're only slightly suspicious you may be having a heart attack, CALL 911 IMMEDIATELY. Believe me, the EMT's will not mind coming to check you out. (I'm speaking from experience here.) They would *much* rather roll on a possible false cardiac alarm early, than arrive too late when you're in full arrest. By the way, even if you've already survived one heart attack, that doesn't make you an expert! Your next one could present a completely different set of initial symptoms. And, if you're a woman, you're at special risk. Heart disease is the number one killer of American women (it's also the #1 killer of men). However, women not only tend to ignore symptoms more frequently than men, they also delay seeking assistance/treatment more than men. That's a bad combination. There are other differences. Women heart attack victims tend to be about 10 years older than men. Women are more likely to have other preexisting conditions, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and congestive heart failure. Womens' most common heart attack symptom is chest pain or discomfort. But women are somewhat more likely than men to experience shortness of breath, and/or stomach, back or jaw pain. About Your Risk About Aspirin About AED's Thank you for reading this article. |